Does Your Midnight Snack Cause Cancer?

“If we shouldn’t eat at night, why is there a light in the fridge?”

Key Takeaways

Eating at night can’t possibly cause you to directly gain fat.

New accusations against late night eating include:

Increasing risk for cancer/cancer recurrence

Increasing levels of chronic inflammation

Increasing blood sugar and reducing insulin sensitivity

Nutrient timing may very well play a role in cancer etiology, and a lifestyle that aligns with our natural circadian rhythm will likely optimize health and longevity

It appears that late meal timing slightly increases cancer risk in a subset of the population, but there are too many unexplained variables and nuance to definitively state that it causes cancer in otherwise healthy people.

It is more than likely that other lifestyle and nutrition factors, including energy balance, food composition, and macronutrient breakdown, are simply more important than nutrient timing for overall health and longevity

Full Story

As a health and fitness professional, many assume that I go through life as a regimented robot programmed by the latest Pub Med research. People think that if one morsel of refined carbs or sip of alcohol crosses my lips it will short circuit my motherboard and cause a total malfunction. Some won’t believe me, but I am not nearly that strict.

I wouldn’t exactly describe myself as flexible or even easygoing, but I take a calculated approach to the aspects of my lifestyle in which I choose to exchange short term pleasure for long term health optimization. For every choice I make, whether it be about my training, nutrition, or recovery - I do a cost-benefit analysis to mitigate the negative health risk. The areas that I decide to “splurge” in are ones that add value to my life and, based on the available evidence, do not significantly threaten my goals or health.

Usually, my internal mitigation sheds light on any given question and allows me to make a clear decision. For example:

Two alcoholic drinks a few times a month? —> Oh sure.

Frequent egg and red meat consumption? —> You got it.

Daily artificial sweetener intake? —> Go right ahead!

Eating at night? —> ???

I continue to go back and forth on this one pesky topic, leaving me unsure if I’m making a compromise in the right spot or doing serious damage to my long term health. Is a late night meal a harmless habit or a damaging, cancer causing, inflammation increasing, blood sugar spiking nightmare?

Eating at Night Doesn’t Cause Fat Gain

In “Eating at Night Part 1: I’ve Changed My Mind” we established that, due to the laws of thermodynamics, eating at night can’t possibly cause you to directly gain fat.

Energy balance = calories in - calories out

We then went on to explore the concept that eating at night may disrupt sleep and result in a cascade of harmful hormonal and metabolic effects. But after testing it myself in an n of 1 study, a large pre-bed meal hardly affected my sleep quality or recovery (that doesn’t mean it won’t for you).

And we discussed that eating late in the day can make us susceptible to decision fatigue, a phenomenon that explains the decreased quality of our food choices as the day goes on. But for me, a guy that rigidity tracks every bite of food he puts in his mouth, this too was a nonissue.

This was great news! I had a clean conscience and could enjoy my rather large pre-bed snack without any guilt! Ignorance is bliss, and I almost wish I could have lived out the rest of my days not thinking twice about going to bed with a full stomach.

Then, Everything Changed

Just like with the secrets of the birds and the bees and Santa, the acquisition of more information robbed me of my innocence. I made the decision to dig deeper and discovered even more potential downsides to eating at night.

I was devastated. I had heard about these effects on podcasts and skimmed over them in books but never examined them with much depth. The new accusations against late night eating that I now must address include:

Increasing risk for cancer/cancer recurrence

Increasing levels of chronic inflammation

Increasing blood sugar and reducing insulin sensitivity

The Accusations

These are some harsh accusations against the little ole midnight snack and I am not going to sit by and let him be sentenced without a fair trial. Because the midnight snack is an abstract concept -it lacks consciousness, a brain, and a mouth - it can’t possibly defend itself on the stand. To that end, who better to defend him than someone that loves him - me.

Understand my position - I love to enjoy a rather large pre-bed snack and I desperately want to keep it as a part of my routine. After acknowledging and understanding my bias, I am going to ensure that I take an objective approach to this trial. If I rule against the midnight snack, you can rest assured my decision is well supported by the available evidence (yes, I am the lawyer, judge and jury. I know it’s confusing but Solokas Focus is a one man show.)

Each accusation is jarring and will require a comprehensive analysis. As they say, there is only one way to eat an elephant - one bite at a time. Let’s break it down into three sections and look at the effect of late night eating on:

Cancer risk (today)

Inflammation (later)

Metabolic health (even later)

First up, the accusation that late night eating increases cancer rates/recurrence rate.

What Affects Your Cancer Risk?

In general, a large portion of the most common cancers can be attributed to smoking, high body weight, a sedentary lifestyle, and poor nutrition (1). Though there are genetic and environmental components of many forms of cancer, it is clear that lifestyle and diet choices are drivers of not only cancer but also many other chronic diseases. While nearly everyone knows that what we eat can affect our cancer risk, new research is shedding light on the fact that when we eat may be just as important.

Nutrient timing may very well play a role in cancer etiology, and a lifestyle that aligns with our natural circadian rhythm will likely optimize health and longevity (2, 3). There is little doubt that circadian biology plays an important role in the development of disease.

It has long been established that circadian dysfunction in the form of night shift work, jet lag, and sleep disruption can result in increased rates of breast, prostate, colon, liver, lung, and pancreatic cancer (4-12). Additionally, it appears that circadian dysfunction is associated with reduced efficacy of cancer treatment and increased cancer mortality (13-15).

The research supporting the adverse effect of circadian rhythm disruption on cancer risk and outcomes is pretty damning against the midnight snack. But for all intents and purposes, the question becomes, “Is it fair to consider late night eating a form of circadian dysfunction?”

It certainly follows that eating at an “unnatural” time could result in similar harmful effects, albeit perhaps not to the same degree. Let’s now take a look at the research more specific to nocturnal eating habits and cancer risk/recurrence rate.

Isolating the Variables

Understandably, there is significantly less research assessing the impact of a late night meal on cancer risk than the effect of shift work/complete circadian dysfunction. With complete circadian dysfunction, researchers are able to look at entire populations of human shift workers or insomniacs, or make mice live in opposition to their natural rhythm, and note the general rates of disease/disease progression compared to the rest of the population.

It is much more complicated to isolate the effect of late night eating in human trials. Just a few of the aspects of a more narrowed human nutrition study assessing a single variable (in this case, nutrient timing) that researchers must consider include:

Overall food intake + bodyweight changes

Food composition

Genetic variability + family history

Accuracy of self reported dietary intake

Additionally, every study is subject to the following fallacies:

Correlation does not equal causation

A few studies do not prove that a theory is true

Studies are a lot more interesting (and profitable) if they are able to support a new or exciting theory. Thus, researchers are likely to manipulate the raw data to claim headline worthy findings.

As you can see, nutrition is a complicated field. The difficulty to perform accurate studies in this area is part of the reason that the entire country has been given, by the experts, faulty dietary recommendations throughout the history of the U.S. I’m not claiming to have all the answers, but it is certainly a fact that nutrition research is complicated and we should not blindly trust the findings of any individual study.

To then combine nutrition with perhaps the most nuanced and perhaps least understood disease in all of medicine, cancer, becomes a gargantuan task. But we’re going to try our best.

Food Pyramid from the 1940’s (16).

What Does the Research Show?

Study #1 - “Adherence to diurnal eating patterns and specifically a long interval between last meal and sleep are associated with a lower cancer risk…” (Kogevinas et al. 2018)

Let’s move on to the good stuff. In humans, it has been shown that late night eating increases one’s risk for developing cancer and increase cancer recurrence rate. Specifically, this study that made its way into many headlines found that those that ate their final meal before 9pm or waited at least two hours after their final meal to go to bed had a 26% lower risk of developing prostate cancer and a 16% lower risk of developing breast cancer, compared to those that ate after 10pm or close to bedtime (17, 18).

It is difficult to isolate specific risk factors because cancer is a multifactorial disease, but the researchers took care to adjust for many variables. They accounted for family history and socioeconomic status and still found that late night eating significantly increases one’s risk.

Limitations

That being said, a few qualms I have with this particular study include:

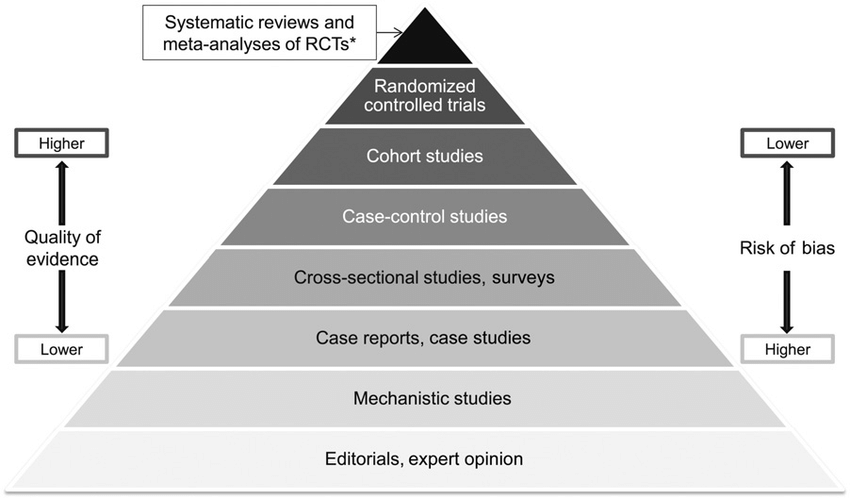

It was an observational case control study. This means that they compared those with cancer to a control group that did not have cancer and tried to identify trends that may have led to the development of the disease. Case control is a quality study method, but not as high quality as cohort studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), or systematic reviews of RCTs.

The study subjects were interviewed about their meal frequency and sleep habits. Some researchers claim that memory based dietary reports are unreliable while others claim that it is the foundation of nutrition studies (20, 21).

Regardless of the reliability, there are reasons to be skeptical about self reported dietary intake. It is human nature to for people to bias self-reported surveys to make themselves look better and healthier. It is not unreasonable to speculate that, for example, those reported finishing eating at 9pm actually finished at 10 or 10:30pm, those that claimed they waited three hours after dinner to go to bed actually only waited 2 hours, etc.

The researchers state:

“Although the circadian pattern questionnaire is extensive and requested information for different time periods in life and separately for weekdays and weekends, the retrospective assessment of eating patterns is the main limitation of the study. The reliability of retrospective assessment of food consumption has well known limitations. Even large cohort studies on food consumption have provided markedly different results on diet and cancer. Dietary data might be subject to measurement error; nevertheless, we used a previously validated FFQ for Spanish populations, and aggregated food group data was corrected using cross‐check questions.33, 34 Nonetheless, it could be expected that questions on timing of eating, for example, “At what time do you usually have supper?” are better recalled than detailed retrospective data on specific foods. However, there are limited population data on timing of eating patterns and on validity of the questions on timing and to this extent the degree of misclassification is unknown.”

While the researchers did account for BMI and smoking, they did not adjust for daily energy intake, food composition, alcohol consumption, or physical activity levels - four of the most important cancer risk factors (22).

The subject matter is a newly studied topic and the study findings have not been replicated. The study, published in 2018, also claimed, “This is, to our knowledge, the first epidemiological study showing long term health effects associated with mistimed eating patterns.” Findings, especially in nutrition, must be replicated in order to be considered reliable.

The other limitations of this study include:

“A further limitation of the study is that variability in meal timing in our population was fairly small and although this does not bias effect estimates it may affect precision.”

“Finally, although the study is not small, confidence intervals for some of the associations particularly in stratified analyses are fairly wide. Findings should be replicated if data are available, in cohort studies.”

Hierarchy of quality of evidence (19).

I’m not going to break down every study in such depth because it would take way too long, but you get the idea. Just because a study claims a finding and news outlets put it in headlines does not mean it is fact.

Despite its limitation, this particular study may still have some merit. The researchers adjusted for many variables, found a significant relationship between rates of prostate cancer and self reported late night food intake, and the findings align with hypotheses based on previous circadian dysfunction research.

Study #2 - “Prolonging the length of the nightly fasting interval may be a simple, nonpharmacologic strategy for reducing the risk of breast cancer recurrence.” (Marinac et al. 2016)

This 2016 study of people with early stage breast cancer found that fasting for <13 hours/night was associated with a 36% higher risk of breast cancer recurrence rate compared to those that fasted 13 or more hours per night. Interestingly enough, short overnight fasts did not significantly correlate with cancer mortality or all cause mortality (23).

Limitations

The authors admit:

“Nonetheless, the use of self-reported dietary data is also a limitation, as recalls are prone to numerous biases. However, it is unknown whether self-reported timing of energy intake is susceptible to similar biases. We also relied on self-reported data for sleep duration, physical activity, and comorbidities, which may be subject to error… Finally, our study included multiple primary end points for breast cancer prognosis (ie, breast cancer recurrence, breast cancer–specific mortality, and all-cause mortality). Because this was an exploratory analysis of a novel association for a modifiable risk factor, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons. Therefore, there could be an increased probability of a type I error.”

Once again, although the study reported a significant association between late night eating and breast cancer recurrence, it failed to account for many crucial confounding variables.

More Studies

Other studies have found similar associations between late night eating and increased cancer risk (24, 25, 26).

This study of 332 hospital patients (half diagnosed with colon cancer, half age and gender matched control subjects with no history of cancer or other chronic disease), found that a shorter dinner-to-bed period (<3 hours) was associated with increased risk of colorectal cancer. The limitations of this study include:

“1st, the choice of the study subject was limited to 1 hospital, which needs to expand the scope of investigation and increase the sample size. Second, as with all retrospective case-control studies, this study had a bias of recall and selection. Third, the control group were healthy residents visiting the same hospital for annual health check-ups, so they may have better health consciousness and habits than case group. Finally, we did not include several other variables, such as the use of drugs (anti-inflammatory drugs), working hours, and diet structure; these factors should be included in future research” (27).

Research - The Bottom Line

Without a doubt, each study linking late night eating and cancer risk has its strengths and weaknesses. It appears that late meal timing slightly increases cancer risk in a subset of the population, but there are too many unexplained variables and nuance to definitively state that it causes cancer in otherwise healthy people.

Final Ruling

To prevent cancer, is it likely a good idea to stop eating 2-3 hours before bed and to consume most of your calories during daylight hours? Yes. Is eating a snack 2 hours before bed going to have a strong enough of an effect to directly cause cancer? Probably not.

The most important lesson that I have re-learned while researching for this article is that the research-backed, big picture habits are the most important facilitators of health or drivers of disease. The BIG ROCKS of health include:

Overall Nutrition

Calorie Balance (eating enough to maintain for a healthy weight)

Food Composition (healthy vs. less healthy food)

Macronutrient Amounts (eating the right amounts of protein, fat, and carbs)

Regular Exercise and Daily Movement

Quality Sleep

Management of Stress Levels

Abstaining from Smoking and Excessive Alcohol Intake

As nutrition is an ever-changing field, it is easy to get caught up in the minutiae. The bottom line is this: while timing of food intake is a very new and exciting area of research, we mustn't miss the forest for the trees and cause ourselves undue stress about less important factors of health and longevity.

If you’re interested in learning more about the most important aspects of nutrition for our health, check out this brief TED Talk by Dr. Mike Isratel about the “Scientific Landscape of Healthy Eating" (TRUST ME- it’s worth the 14 minutes) (28).

The hierarchy of nutritional aspects important for health (29).

Wrap Up

At this point, keeping in mind the strength of the available evidence, I feel comfortable taking the following stance on late night eating and cancer risk -

For someone that:

Maintains a healthy body weight

Consumes mostly nutritious foods

Trains with high intensity 3-5x/week

Gets 10,000+ steps/day

Sleeps 7-9 hours/night

Keeps stress levels low

Doesn’t smoke or consume excessive amounts of alcohol

…finishing food consumption 1 hour before bed compared to 3 or more hours before bed will not significantly increase cancer risk.*

Nutrient timing and circadian biology are novel areas of research and there is much left to be further studied. The fact remains that it is more than likely that other lifestyle and nutrition factors, including energy balance, food composition, and macronutrient breakdown, are simply more important than nutrient timing for overall health and longevity.

*(Remember - I’m not a doctor, cancer researcher, or registered dietician. Please do not take my opinion as medical advice!).

To be continued…

With all of the background information out of the way, “Eating at Night Part 2B” will be a much shorter and focused article. Keep an eye out in the coming months for a deep dive on the next accusation against the midnight snack - late night eating increases systemic inflammation.

Sources:

https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2018/targeting-circadian-clock-cancer

https://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/79/15/3806#ref-10

https://www.choosemyplate.gov/eathealthy/brief-history-usda-food-guides

https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(15)00394-8/pdf

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=youtu.be&v=TYeZVfPxwKM

https://renaissanceperiodization.com/introducing-healthy-diet-templates/